Photo by Bruce Kirchoff licensed under CC BY 2.0

I sure do love me a good oak. Moving to the Midwest of North America has given me the opportunity to meet many new oak species. One oak that has captured my attention in recent years is the overcup oak (Quercus lyrata) whose both common and scientific names first attracted me to this wonderful tree.

Let’s start by looking at the scientific name of this species. The specific epithet “lyrata” was given to this tree because its leaves are said to resemble a lyre. Having no familiarity with popular instruments of Ancient Greece, I had to look this one up. Personally, I have a hard time seeing the resemblance in most leaves. Perhaps this is because the leaves on any given tree can be highly variable in both shape and size depending on both where they are positioned in the canopy and where the tree itself is rooted.

Photo by Bruce Kirchoff licensed under CC BY 2.0

The name “overcup” comes from the fact that the caps of each acorn nearly encompass the entire seed. It is neat to see a mature acorn of this species as they appear to be immature at all stages of development. The odd morphology of these acorns has everything to do with where these trees grow in nature and the way in which they manage seed dispersal.

Photo by Bruce Kirchoff licensed under CC BY 2.0

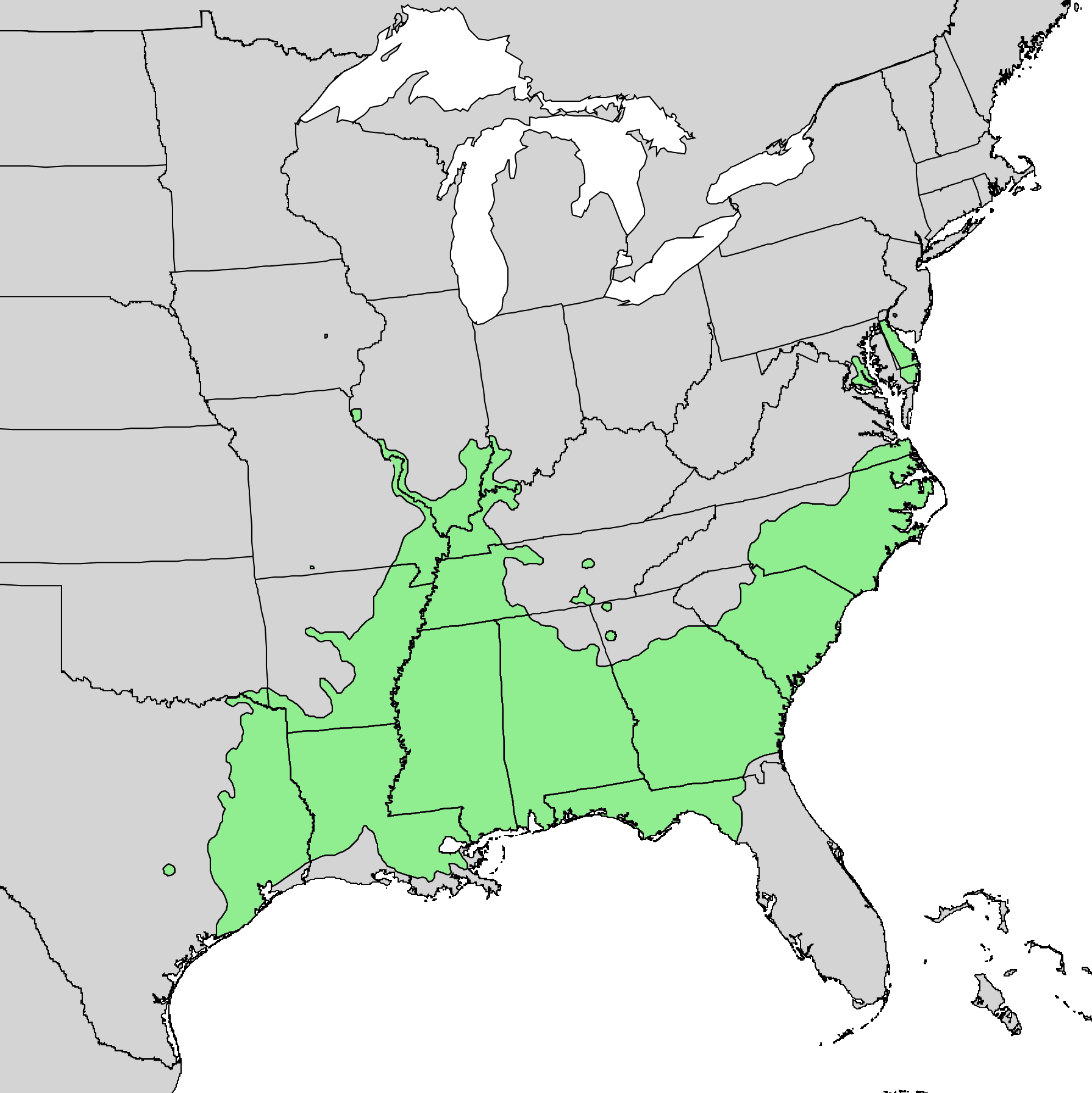

Overcup oak is one of the most flood tolerant oaks in all of North America. In fact, it most often grows in around wetlands and in floodplains throughout south-central portions of the continent. As such, this species has evolved to tolerate and take advantage of periodic flooding from one year to the next. Not only can mature trees handle weeks of having their roots and trunks completely submerged, the overcup oak also utilizes flooding as a means of seed dispersal.

The cap that covers each seed is very corky, which causes the acorns to float. This is good news for the seeds as young trees have a hard time making a living in the shade of their parents. Historically, floods would pick up and move overcup acorn crops and, with any luck, deposit the acorns in a new floodplain where disturbance has cleared enough spots in the canopy for the acorns to germinate and grow into vigorous young saplings.

USGS/Public Domain

Speaking of germination, overcup oaks are unique among the white oak tribe in that their seeds exhibit a prolonged dormancy. Normally, acorns of the various white oaks germinate in the fall, not long after they were shed from the trees above. However, living in areas prone to flooding would make germinating at that time of year a risky endeavor. As such, overcup oak acorns lay dormant for months until some environmental cue(s) signals enough time has passed.

Overcup oak is also extremely intolerant of fires. Even modest sized burns can severely damage or kill all but the largest individuals. Normally, the forests in which these trees grow are too wet to produce large fires but prolonged droughts and altered flood regimes can change those dynamics to such a degree that large swaths of overcup oak can be killed.

In fact, altered flooding regimes are one of the biggest threats facing overcup oaks in their native range. Because we have dammed, diverted, and channeled so many waterways in North America, the floods that once maintained overcup oak habitats have changed in a big way. Without regular flooding to disperse their seeds and reduce competition from the canopy above, overcup oaks are having a much harder time regenerating. Saplings gradually dwindle in the shade of their parents and, where rivers do continue to flood, these events are often much more severe than they were in the past. Saplings that aren’t tall enough to rise above the floodwaters eventually drown. Overcup oak may be tolerant of flooding but it is by no means its preferred way to live.

Despite these challenges, overcup oak is still a prominent member of seasonally flooded forests throughout its range. It is a magnificent species well worth spending the time to become familiar. It can also make an excellent specimen tree in all but the driest of south-central North American soils. Also, because it is an oak, this incredible species is also chock full of wildlife value, making it an important component of the ecology wherever it is native.

Photo Credits: Bruce Kirchoff [1] [2] (Licensed under CC-BY), U.S. Geological Survey, Chhe, USDA