If the early bird gets the worm, it is only because we haven't been observing bats the right way, at least not in the rainforests of Central America. It has long been thought that insects such as katydids and caterpillars exhibit night feeding in order to escape day-active birds. This theory has influenced the way in which researchers investigate insect herbivory in tropical forests. However, recent studies have shown that bats, not birds, are doing the bulk of the insect eating in both natural and man-made habitats.

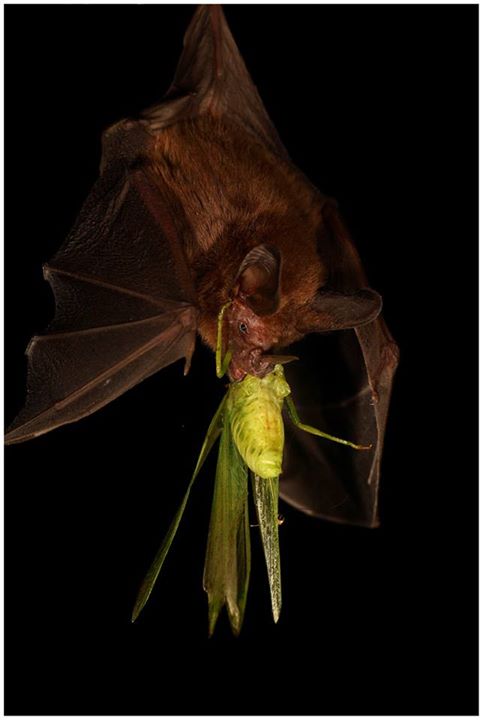

In order to accurately investigate the role of insectivorous bats play in limiting herbivory in tropical forests, researchers decided to look at the common big-eared bat (Micronycteris microtis). They wanted to find out exactly how much insect predation could be attributed to these nocturnal hunters. As it turns out, 70% of the bats diet consists of plant eating insects, which is quite significant. Extrapolating upwards, it was apparent that we have been overlooking quite a bit.

Photo by Christian Ziegler via Santana SE, Geipel I, Dumont ER, Kalka MB, Kalko EKV (2011) All You Can Eat: High Performance Capacity and Plasticity in the Common Big-Eared Bat, Micronycteris microtis (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). PLoS ONE 6(12): e28584. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028584 licensed under CC BY 2.5

Using special exclosures, researchers set out to try to quantify herbivory rates when bats and birds were excluded. What they found was staggering. When birds were excluded from hunting on trees, insect presence went up 65%. When bats were excluded, insect presence skyrocketed by 153%! What this amounts to is roughly three times as much damage to trees when bats are removed - a significant cost to forests.

To prove that it wasn't only natural forests that were benefitting from the presence of bats, the researchers then replicated their experiments in an organic cacao farm. Again, bats proved to be the top insect predators, eating three times as many insects than birds. This amounts to massive economic benefits to farmers. Bats have long been viewed as the enemies of both the farm as well as the farmers. Research like this is starting to change such perspectives.

This certainly doesn't diminish the role of birds in such systems. Instead, it serves to elevate bats to a more prominent stature in the healthy functioning of forest ecosystems. Findings such as these are changing the way we look at these furry fliers and hopefully improving our relationship as well.

Photo Credit: Christian Ziegler - Wikimedia Commons

Further Reading: [1] [2]