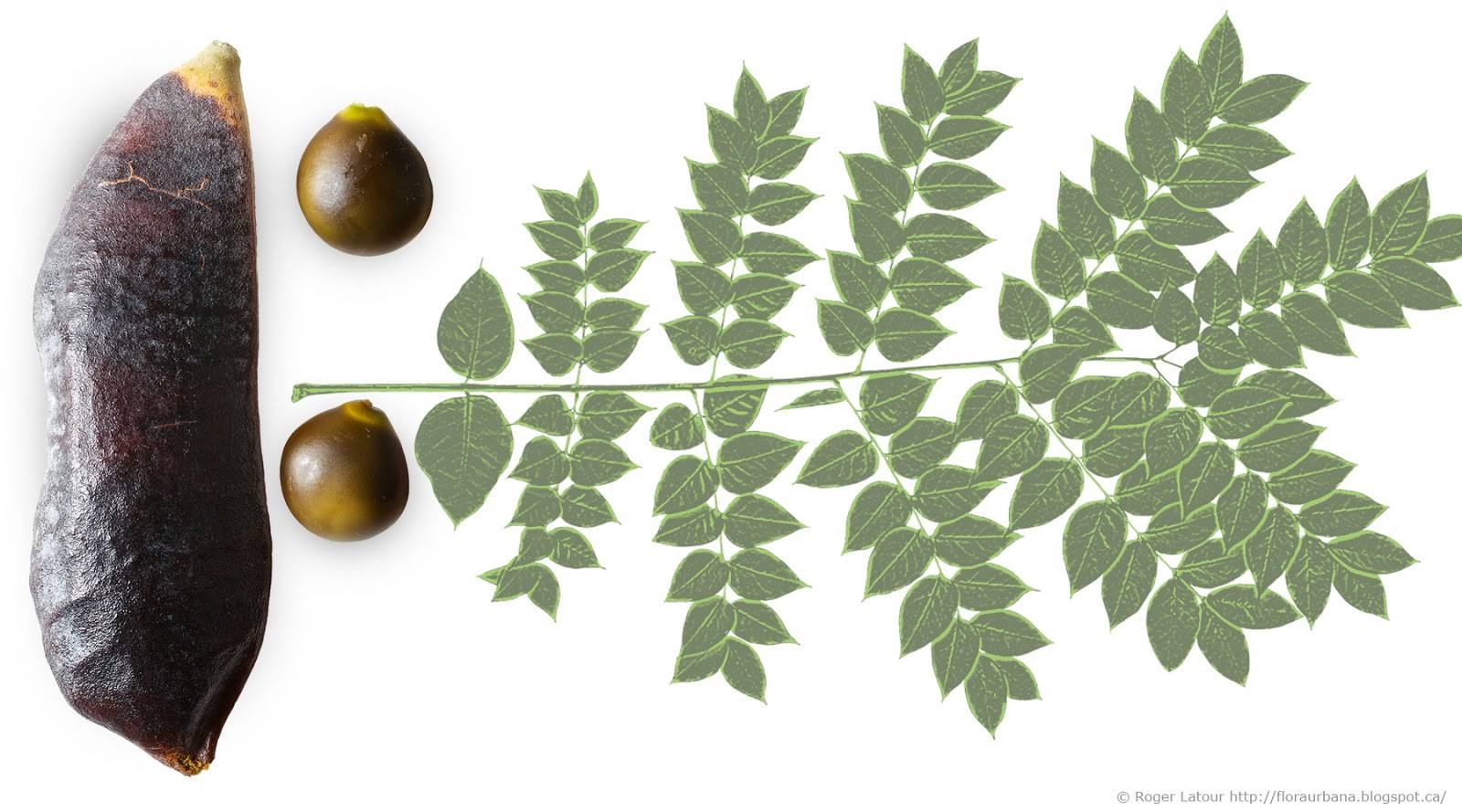

Photo by Flora Urbana

To see a Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) in the wild is a rare event. Each year your chances of doing so are diminishing. This interesting and beautiful legume is quite rare, growing in small scattered populations throughout eastern and Midwestern North America. Presettlement records hint that its rarity in nature is not necessarily a recent phenomenon either. It seems that, at least since humans have been paying attention, this tree has always been scarce.

Despite its rarity in the wild, the Kentucky coffee tree has gained a lot of popularity as a landscape tree. It is an attractive species with contorted branching and large, airy leaves. It's about this time of year when folks start wondering if they have killed the new tree they planted last fall. I often hear complaints from folks new to this species that their trees must have lost their buds over the winter. The reason for this lies in its generic name. "Gymnocladus" is Greek for "naked branch." The leaf buds are not exposed like they are in other tree species. Instead, they are imbedded within the twigs, hidden under a hairy ring of bark. Kentucky coffee tree does not leaf out until late spring, well after most other trees have broken dormancy.

In the wild, Kentucky coffee tree can be found growing on floodplains and, very occasionally, scattered through upland habitats. As such, water has been invoked as the only known dispersal agent. This is a strange mechanism to call on as nothing about this tree (other than its current habitat) suggests adaptations for water dispersal. Its seed pods are quite heavy, chock full sweet pulp, and don't float very well. What's more, the pods often remain on the tree all winter and the large seeds within require ample scarification before they will germinate. They are toxic to boot.

Even more perplexing is just how well this species does when planted outside of floodplains. It seems equally at home growing in a yard or along the sidewalk as it does on a floodplain. Taken together, all of these clues seem to suggest that the Kentucky coffee tree is missing something. Perhaps it is missing a preferred seed disperser?

The megafaunal dispersal syndrome has become a sexy topic in ecology. Essentially it posits that North America was once home to a bewildering array of large mammals that flourished leading up to the end of the Pleistocene. With that many large animals haunting this once wild continent, many have suggested that North American vegetation evolved to cope with and even exploit their presence. Certainly we see this happen on a smaller scale with things like birds and small mammals. We see it on a much larger scale with animals like elephants and rhinos in Africa and Asia. Could it be that when the Pleistocene megafuna went extinct in North America, the plant species they dispersed suffered a huge ecological blow?

The limited range of species like the Kentucky coffee tree would certainly seem to suggest so. Though it is a hard theory to test, the fruits of this tree seem adapted to something much more specific than running water. The large pod, the sweet pulp, and the hard seeds would suggest that the Kentucky coffee tree requires a larger mammalian herbivore to eat, scarify, and pass its seeds. No animal native to this continent today does the trick effectively. Most animals avoid the seeds entirely, which is likely due to their toxicity. Sure, the occasional seed germinates successfully, however, based on its limited natural range, the fecundity of the Kentucky coffee tree has been diminished.

Photo Credit: Roger Latourwww.floraurbana.blogspot.ca

Further Reading: