Photo by Sugeesh licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

Grasses dominate our planet today but that has not always been the case. Because of both their ecological and cultural importance , the origin and diversification of grasses has long been a hot topic in biology. We know that grasses really hit their stride following the extinction of the dinosaurs, and that they changed herbivore anatomy in a big way, but their origins remain shrouded in mystery. Recently, a discovery made in fossilized dinosaur poop has shone a surprisingly bright light into the history of grasses on our planet.

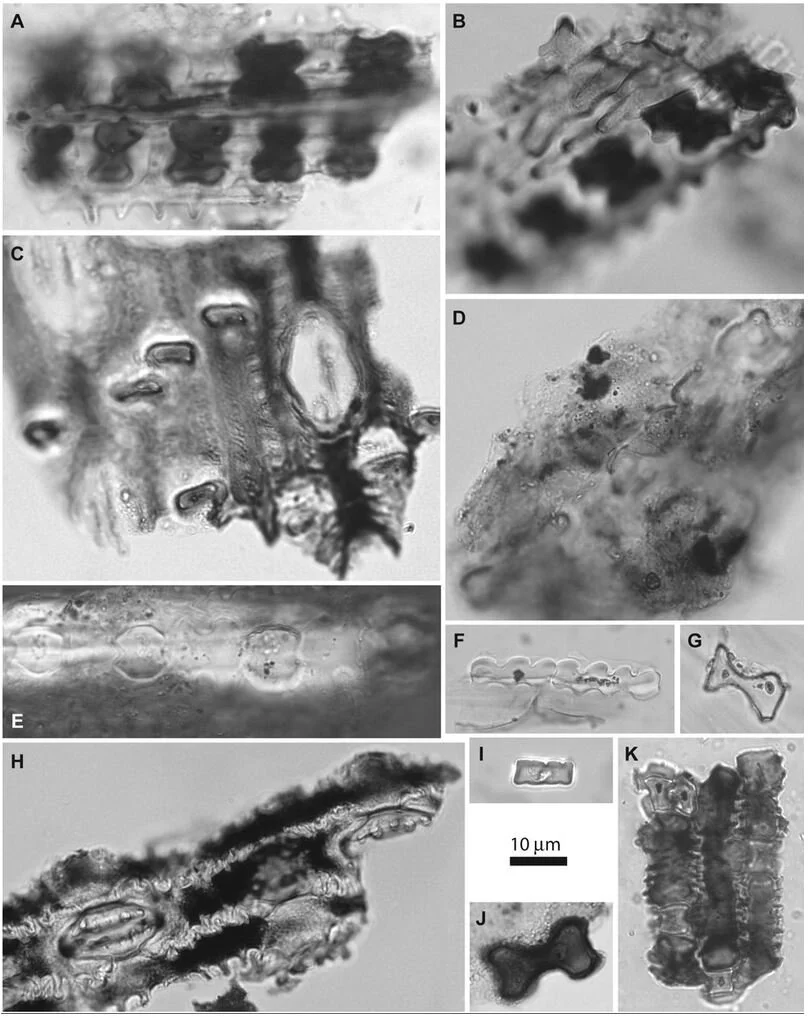

Prior to this discovery, the earliest evidence of grasses came in the form of fossilized pollen and tiny pieces of silica called phytoliths. Phytoliths are essentially tiny pieces of glass that serve as a form of defense against herbivores. Because they are made of silica and fossilize well, phytoliths turn up frequently in the fossil record. This makes them extremely useful for finding evidence of grasses even where whole-plant fossilization is unlikely.

Illustration by Nobu Tamura (http://spinops.blogspot.com) licensed by CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Whereas phytoliths are not unique to grasses, their form is often taxon-specific. With a good eye and a bit of training, one can look at a phytolith under a microscope and tell you what type of plant it came from. This is where the dinosaur poop comes into the picture. By examining fossilized dinosaur poop from India, paleontologists can get an idea of what dinosaurs were eating.

By examining the fossilized poop of a group of large herbivorous dinosaurs called Titanosaurs, paleontologists now have a better idea of grass diversity in the late Cretaceous. They have uncovered a surprising diversity of phytoliths, which demonstrate that at least 5 distinct grass taxa that we would recognize today were alive and well some 100.5 to 66 million years ago. These include extant groups like Oryzoideae (think rice and bamboo), Puelioideae, and Pooideae (think wheat, barley, oat, rye, and many lawn and pasture grasses). There were other lesser known lineages mixed in there as well.

Fossilized dinosaur poop or “coprolite.” USGS Public Domain

These findings are exciting for a variety of reasons. For one, it tells us that despite lacking teeth specialized for eating grasses, large herbivorous dinosaurs like the Titanosaurs were nonetheless incorporating these plants into their diet. It also tells us that grasses were already quite diverse by the late Cretaceous. The fact that modern clades of grass were around back then sets back grass evolution many millions of years. It also tells us something about grass biogeography. It suggests that grasses were already wide spread across the supercontinent of Gondwana long before India broke away. Finally, it tells us that grasses evolved silicate phytoliths long before more recognizable grass-eating herbivores came onto the scene.

I am always blown away by the details paleontologists are able to extract from such tiny fossils. Who knew dinosaur poop could tell us so much?

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4]

Further Reading: [1]