The leading cause of extinction on this planet is loss of habitat. As an ecologist, it pains me to see how frequently this gets ignored. Plants, animals, fungi - literally every organism on this planet needs a place to live. Without habitat, we are forced to pack our flora and fauna into tiny collections in zoos and botanical gardens, completely disembodied from the environment that shaped them into what we know and love today. That’s not to say that zoos and botanical gardens don’t play critically important roles in conservation, however, if we are going to stave off total ecological meltdown, we must also be setting aside swaths of wild lands.

There is no way around it. We cannot have our cake and eat it too. Land conservation must be a priority both at the local and the global scale. Wild spaces support life. They buffer life from storms and minimize the impacts of deadly diseases. Healthy habitats filter the water we drink and, for many people around the globe, provide much of the food we eat. Every one of us can think back to our childhood and remember a favorite stretch of stream, meadow, or forest that has since been gobbled up by a housing development. For me it was a forested stream where I learned to love the natural world. I would spend hours playing in the creek, climbing trees, and capturing bugs to show my parents. Since that time, someone leveled the forest, built a house, and planted a lawn. With that patch of forest went all of the insects, birds, and wildflowers it once supported.

Scenarios like this play out all too often and sadly on a much larger scale than a backyard. Globally, forests have taken the brunt of human development. It is hard to get a sense of the scope of deforestation on a global scale, but the undisputed leaders in deforestation are Brazil and Indonesia. Though the Amazon gets a lot of press, few may truly grasp the gravity of the situation playing out in Southeast Asia.

Deforestation is a clear and present threat throughout tropical Asia. This region is growing both in its economy and population by about 6% every year and this growth has come at great cost to the environment. Indonesia (alongside Brazil) accounts for 55% of the world’s deforestation rates. This is a gut-wrenching statistic because Indonesia alone is home to the most extensive area of intact rainforest in all of Asia. So far, nearly a quarter of Indonesia’s forests have been cleared. It was estimated that by 2010, 2.3 million hectares of peatland forests had been felled and this number shows little signs of slowing. Experts believe that if these rates continue, this area could lose the remainder of its forests by 2056.

Consider the fact that Southeast Asia contains 6 of the world’s 25 biodiversity hotspots and you can begin to imagine the devastating blow that the levelling of these forests can have. Much of this deforestation is done in the name of agriculture, and of that, palm oil and rubber take the cake. Southeast Asia is responsible for producing 86% of the world’s palm oil and 87% of the world’s natural rubber. What’s more, the companies responsible for these plantations are ranked among some of the least sustainable in the world.

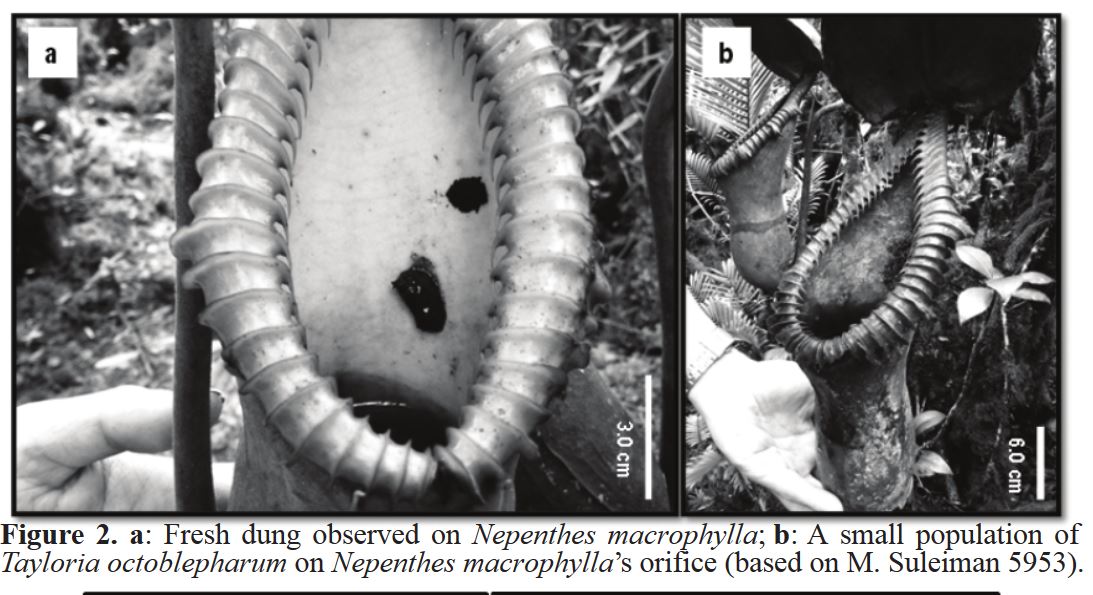

Borneo is home to a bewildering array of life. Researchers working there are constantly finding and describing new species, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. Of the roughly 15,000 plant species known from Borneo, botanists estimate that nearly 5,000 (~34%) of them are endemic. This includes some of the more charismatic plant species such as the beloved carnivorous pitcher plants in the genus Nepenthes. Of these, 50 species have been found growing in Borneo, many of which are only known from single mountain tops.

It has been said that nowhere else in the world has the diversity of orchid species found in Borneo. To date, roughly 3,000 species have been described but many, many more await discovery. For example, since 2007, 51 new species of orchid have been found. Borneo is also home to the largest flower in the world, Rafflesia arnoldii. It, along with its relatives, are parasites, living their entire lives inside of tropical vines. These amazing plants only ever emerge when it is time to flower and flower they do! Their superficial resemblance to a rotting carcass goes much deeper than looks alone. These flowers emit a fetid odor that is proportional to their size, earning them the name “carrion flowers.”