I’ve grown to really appreciate cucurbits (family Cucurbitaceae) in recent years. From their ambling/climbing habit and often delicious fruits to their beautiful flowers and intimate relationships with a few native bees, this family has a lot to offer. Of course, there are few better ways to get to know plants than by growing them in and around your home and, at least at our place, this summer will go down in history as the summer of the gourd. We are currently growing a handful of species and cultivars and I get a great deal of enjoyment out of watching them grow up the trellis we have provided.

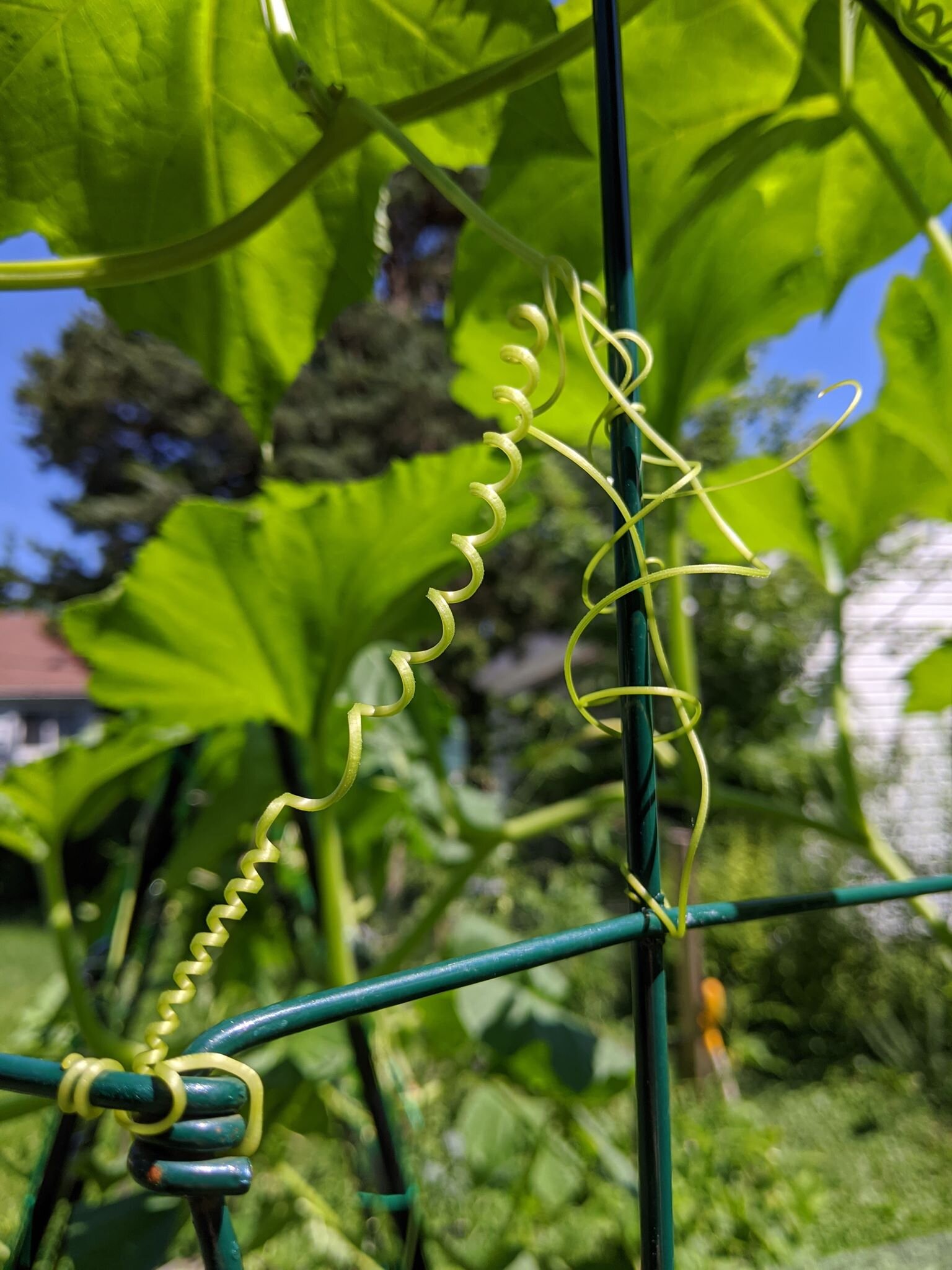

As they climb, cucurbits send out long, thin tendrils (which are actually modified stems) that grab on and wind around any surface they touch. This happens surprisingly quick too. Within only a few minutes of touching a surface, individual tendrils will begin to wind themselves around it. This phenomenon has fascinated people for centuries. I don’t doubt it amused the indigenous cultures that first began cultivating them for food and that amusement continues till this day. Do a web search for cucumber tendrils and you will find countless pictures and blogs showcasing this wonderful anatomical habit.

Despite all the attention, the mechanisms behind this behavior have largely remained a mystery until quite recently. We have known that the initial curling of the tendril is induced by touch. As soon as the cells within the tendril sense contact with a surface, the signal is sent to begin curling. But how do they curl so quickly?

The key to this behavior lies in a two-layered band of specialized cells that run the length of the tendril. Once the signal that the tendril has touched an object has been received, these bands swing into action. One layer of cells will immediately begin to expel water, causing them to contract. Meanwhile, the other layer of cells becomes increasingly stiff and lignified. This creates tension along the length of the tendril, causing it to bend. Oddly enough, this doesn’t happen in the same direction. Take a close look at the tendrils on a cucumber or squash vine and you will notice that each tendril curls in two different directions, separated by a kink or “perversion” (as it is known in the literature) in the middle. This is because the layer of cells on the band that shrinks is different whether you are near the tip or near the base of the tendril.

As many of you reading this are already well aware, the tendrils help to secure the plants as they climb. However, the story is much more interesting than simply anchoring the plants in place. The curling of the tendrils is extremely important when it comes to structural support. If the tendrils did not curl, the plant would be anchored in place with very little wiggle room. As big gusts of wind cause the plant to thrash to and fro or a heavy limb comes crashing down from above, a straight tendril would be far more likely to break under the strain. By adding those opposite twists, the tendrils are able to flex a lot, providing enough movement to keep them from breaking under stress.

If you watch how the tendrils develop over time, their amazing structural support gets even cooler. When stretched, a metal spring looses a lot of its springy-ness. This is not the case for cucurbit tendrils. When stretched, they not only return to their original shape, they curl even tighter. This way, the plant is able to secure itself with varying intensities, allowing for fine tuned adjustments to its structural support. The amount of curling also changes with age. Older tendrils tend to curl more tightly than younger tendrils, especially under strain. As the plant grows, older portions of the stem secure themselves much more strongly via their tendrils. Alternatively, the younger growing portions of the stem need to be a bit more flexible as they anchor themselves to whatever they are climbing on.

So there you have it. The aesthetically pleasing, curly tendrils of your cucurbits serve a very important function in the growth of the plant. Without them, these plants would not only have a hard time climbing, they would also be knocked down by every minor disturbance. The key to their success as vines lies in highly modified stems with an intriguing band of specialized cells that provide them with a physically sound anchoring mechanism.

Learn more in this video:

![Stems climbing on fallen dead wood (a) or on standing living trees (b). A thick and densely branched root clump (c) and thin and elongate roots (d) [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1518471929195-C99KP24U24J238YMX055/myco+roots.JPG)