Photo by Nicola Delnevo [SOURCE]

Ants have struck up a lot of interesting and important relationships with plants. They disperse seeds, protect plants from herbivores and disease, and can even help acquire nutrients. For all of the beneficial ways in which ants and plants interact, pollination rarely enters into the equation. More often than not, ants are actually detrimental to the sex lives of flowering plants. Such is not the case for a rare species of protea endemic to Western Australia called the smokebush (Conospermum undulatum).

The reason ants usually suck at pollination is thanks to a tiny organ called the metapleural gland. For many ant species, this gland secretes special antimicrobial fluids that the ants use to groom themselves. Because ants tend to live in high densities in close quarters, this antimicrobial fluid helps keep their little bodies clean of any pathogens that might threaten their existence. For as good as these fluids are for ants, they destroy pollen grains, rendering them useless for pollination.

Leioproctus conospermi. Photo by Sarah McCaffrey licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

As is so often the case in nature, there are always exceptions to the rule and it seems that one such exception is playing out in Western Australia. While investigating the reproductive ecology of the smokebush, researchers noted that ants were regular visitors to their small flowers. They knew that in drier climates, some ant species have evolved to produce considerably less antimicrobial fluids. The thought is that drier climates tend to harbor fewer microbial pathogens and thus ants don’t need to waste as much energy protecting themselves from such threats. If this was the case in Western Australia then it was entirely possible that ants could potentially serve as pollinators for this plant. Armed with this hypothesis, they decided to take a closer look.

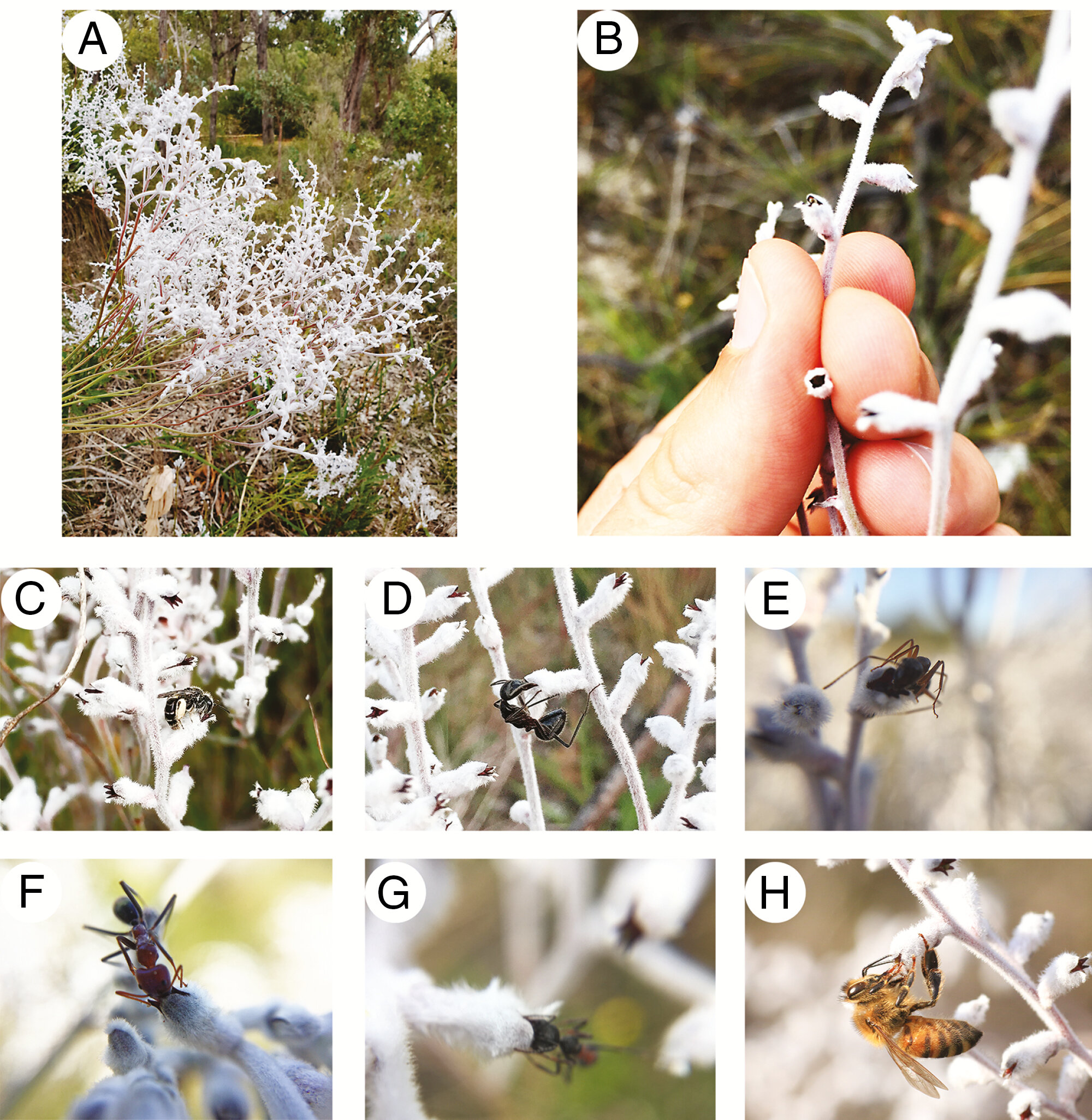

It turns out that the floral morphology of the smokebush lends well to visiting ant anatomy. The tiny flowers produce a small amount of nectar at the base. As ants shove their heads down into the flower to get a drink, it triggers an explosive mechanism that causes the style the smack down onto the back of the ant. In doing so, it also mops up any pollen the ant may be carrying. At the same time, the anthers explosively dehisce, coating the visitor with a fresh dusting of pollen. During their observations, researchers noted that ants weren’t the only insects visiting smokebush blooms. They also noted lots of visitation from invasive honeybees (Apis mellifera) and a tiny native bee called Leioproctus conospermi.

(A) White flowers of Conospermum undulatum. (B) Floral details. (C–H) Insects visiting flowers of C. undulatum: (C) Leioproctus conospermi; (D) Camponotus molossus; (E) Camponotus terebrans; (F) Iridomyrmex purpureus; (G) Myrmecia infima; (H) Apis mellifera. [SOURCE]

After recording visits, researchers needed to know whether any of these floral visitors resulted in successful pollination. After all, just because something visits a flower doesn’t mean it has what it takes to get the job done for the plant. By looking at differences in seed set between ant and bee visitors, they were able to paint a fascinating picture of the pollination ecology of the rare smokebush.

It turns out that ants are indeed excellent pollinators of this shrub, contributing just as much to overall seed set as the tiny native Leioproctus conospermi. Alternatively, invasive honeybees barely functioned as pollinators at all. Their heads were too big to effectively trigger the pollination mechanism of the flowers but nonetheless were able to access the nectar within. As such, honeybees are considered nectar thieves for the smokebush, harming its overall reproductive effort rather than helping.

Amazingly, the effectiveness of ants as smokebush pollinators is not because they produce less antimicrobial fluids. In fact, these ants were fully capable of producing ample amounts of these pollen-killing substances. Instead, it appears that the plant itself has evolved to tolerate ant visitors. Smokebush pollen is resistant to the toxic effects of the metaplural gland fluids. With plenty of hungry ants always on the lookout for food, the smokebush has managed to tap in to an abundant and reliable vector for pollination. No doubt other examples exist, we simply have to go looking.

Further Reading: [1]

![Photo by Nicola Delnevo [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1592594490445-RKITCT8N72D9GVX5TOJP/12349226-4x3-xlarge.jpg)