When someone asks you if you would like to see a wild fever tree, you have to say yes. As a denizen of cold climates defined by months of freezing temperatures, I will never miss an opportunity to encounter any species in its native habitat that cannot survive frosts. This was the scenario I found myself in last week as friend and habitat restoration specialist for the Atlanta Botanical Garden, Jeff Talbert, was showing us around a wonderful chunk of Florida scrubland he has been managing over the last few years.

He drove our small group over to an area that, up until a year or two ago, was completely choked with swamp titi (Cyrilla racemiflora). Like many habitats throughout southeastern North America, this patch of Florida scrub is dependent on regular fires to maintain ecological function. Without it, aggressive shrubs like titi completely take over, choking out much of the amazing biodiversity that makes this region unique. Jeff and his team have been very busy restoring fire to this ecosystem and the results have been impressive to say the least.

We walked off the two-track, down into a wet depression and were greeted by an impressive population of spoon-leaf sundews (Drosera intermedia), which is a good sign that water quality on the site is improving. After a few minutes of sundew admiration, Jeff motioned for us to look upward towards the surrounding tree line. That’s when we saw it. Growing up out of the small seep that was feeding this wet depression was a spindly tree with bright pink splotches decorating its canopy. This was to be my first encounter with a fevertree (Pinckneya bracteata).

A few of us were willing to get our feet wet and were rewarded with a close look at the growth habit of this incredible tree. Clustered at the end of its spindly branches are dark green, ovate leaves that give the tree a tropical appearance. Erupting from the middle of some of those leafy branches were the inflorescences. These are what produce the pink splotches I could see in the canopy of larger individuals. They remind me a lot of a poinsettia and at first, I thought this tree might be a member of the genus Euphorbia. Indeed, the pink coloration comes from a handful of rather large, leaf-like sepals attached to the base of each inflorescence.

Upon seeing the flowers, I instantly knew this was not a member of Euphorbiaceae. Each flower was long and tubular ending in five reflexed lobes. They are colorful structures in and of themselves, adorned with splashes of pink and yellow. After a bit of scrutiny, our group was finally able to place this within its true taxonomic lineage, the coffee family (Rubiaceae).

Within the coffee family, fevertree is closely related to the genus Cinchona. Like Cinchona, the fevertree produces quinine and other alkaloids that are effective in treating malaria. Fevertree has been used for millennia to do just that, hence the common name. It also seems fitting that fevertrees tend to grow in wetland habitats where mosquitos can be abundant. However, this is by no means an obligate wetland species. Those who have grown fevertree frequently succeed in establishing plants in dry, upland habitats as well. Perhaps highly disturbed wetlands are some of the few places where this spindly tree can avoid intense competition from other forms of vegetation.

Fevertrees do need regular disturbance to persist. They are not a large, robust tree by any means and can easily get outcompeted by more aggressive vegetation. However, this species does have a trick that enables individuals to persist when disturbances don’t come frequent enough. Fevertree is highly clonal. Instead of producing a single trunk, it sends out numerous stems in all directions in search of a gap in the canopy. This clonal habit allows it to eek out an existence in the gaps between its more robust neighbors until disturbances return and clear things out.

This clonal habit is also very important when it comes to reproduction. Fevertree requires a decent amount of sunlight to successfully flower and set seed. By using its clonal stems to find light gaps, it can at least guarantee some level of reproduction until fires, floods, or some other form of canopy clearing disturbance frees up enough space for it to prosper and its seeds to germinate. However, its clonal habit can also hurt its reproductive capacity over the long term if recruitment of new individuals does not occur.

Fevertree is considered self-incompatible. In other words, its flowers cannot be pollinated via pollen from a genetically identical individual. As more and more clonal shoots are produced, the tree effectively increases the chances that its own pollen will end up on its own flowers. This is yet another important reason why regular disturbance favors fevertree reproduction. Fevertree seeds need light and bare ground to germinate, which is usually provided as fires and other disturbances clear the canopy and open up bare ground. Only then can enough unrelated individuals establish to ensure plenty of successful pollination opportunities.

With its long, tubular flowers and bright pink sepals, fevertrees don’t seem to have any trouble attracting pollinators, which mainly consist of ruby-throated hummingbirds and bumblebees. Only these organisms have what it takes to successfully access the pollen and nectar rewards of this plant and travel the distances necessary to ensure pollen ends up on unrelated individuals. The seeds that result from pollination are winged and can travel a decent distance with a decent wind. With any luck, a few seeds will end up in another disturbance-cleared wet area and usher in the next generation of fevertrees.

I am so happy that restoration activities at this site are making more suitable habitat for this unique tree. Looking around, we saw many more small individuals starting to emerge where there was once a dense canopy of titi. Hopefully with ongoing management, this population will continue to grow and spread, securing the a future for this species in a region with an ever-growing human presence. If you ever find the opportunity to see one of these trees in person, do yourself a favor and take it!

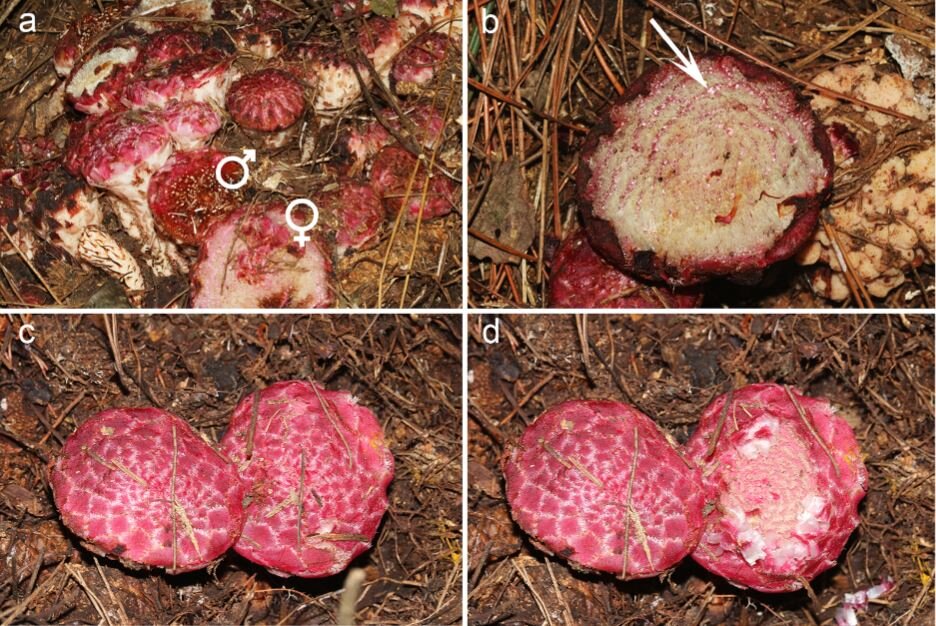

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1615476638537-DVF512X71F5WIY3MR9GT/mcaa204f0001.jpeg)

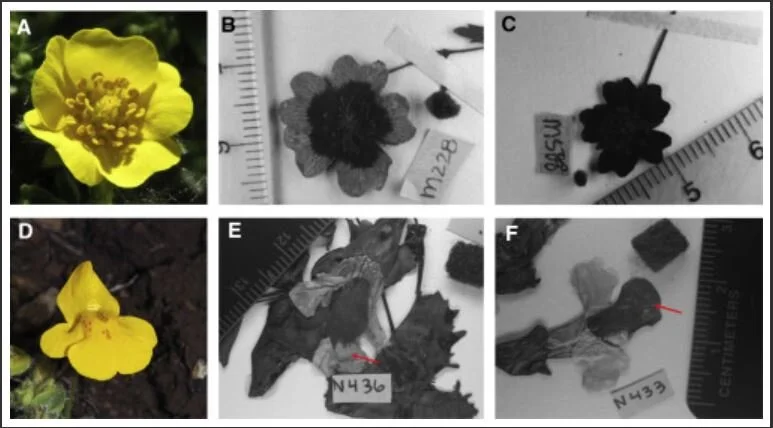

![(A–C) Female Forcipomyia biting midge. Arrows indicating pollen grains. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1602516996716-ICQ7PIZDYU1BOSTTEWJ3/tacca+midge.JPG)

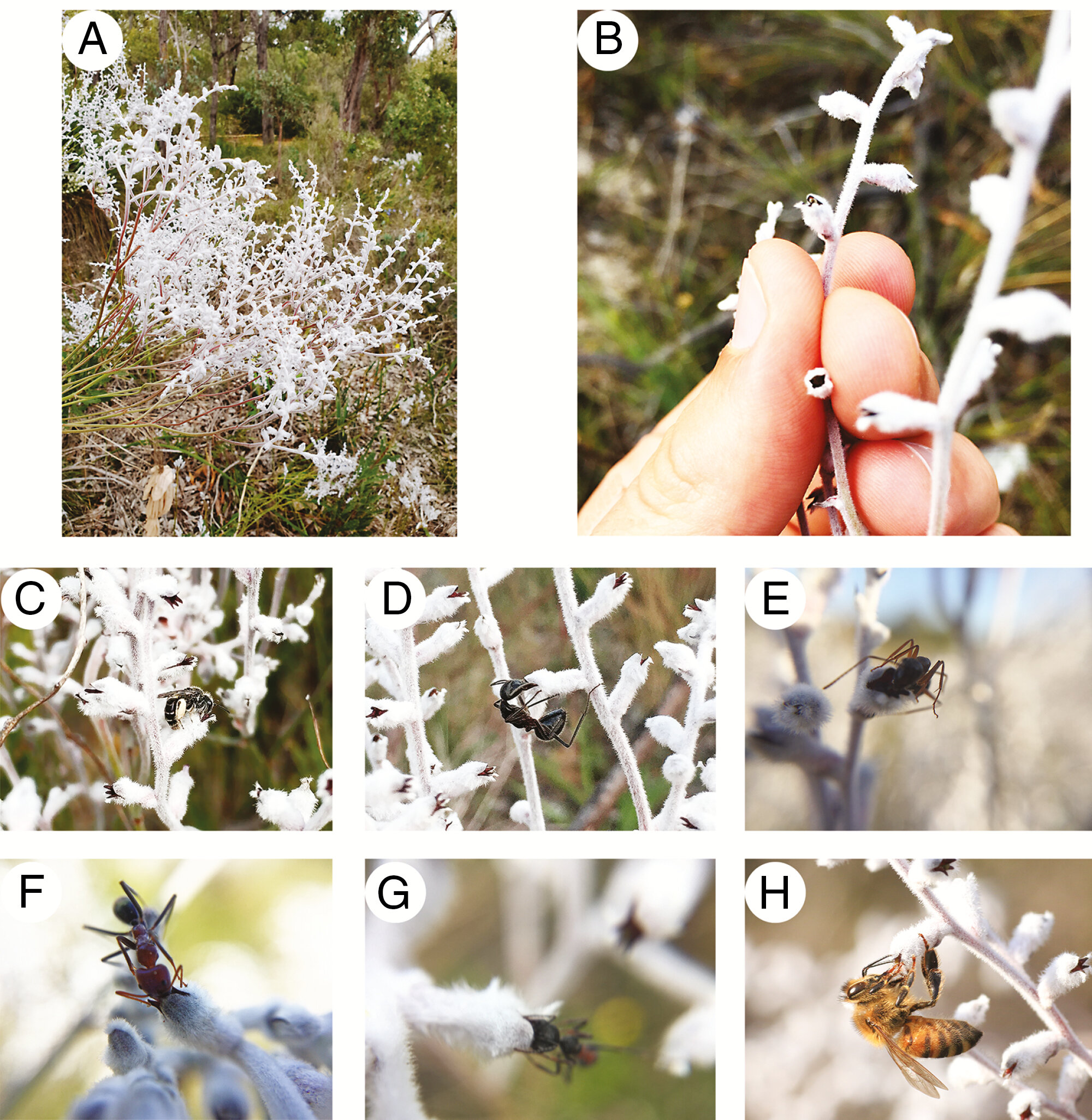

![(1) Immature stamen surround the style; (2) elongation of the style by which the anthers dehisce and pollen grains are swept on the stylar hairs of the immature style; and (3) further outgrowth of the style, anthers are withered. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1597935189988-GZOSOLTMYZR2RB20CDOK/spp.JPG)

![The recently described Cremanthodium wumengshanicum growing at elevation in Yunnan, China. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1595452902740-1SHVHLYLHXN0VGCR17C4/Cremanthodium_wumengshanicum-novataxa_2015-L._Wang-C._Ren_et_Q.E._Yang.jpg)

![Investigating pollinator visitation among different species of Zaluzianskya. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1595453007802-011KTFTH4MG6YEFKCL9M/nph13746-fig-0001-m.jpg)

![Photo by Nicola Delnevo [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1592594490445-RKITCT8N72D9GVX5TOJP/12349226-4x3-xlarge.jpg)

![(A) Sequential images of a worker penetrating a leaf with its proboscis. (B) A worker cutting into a leaf with its mandibles. (C) Characteristic bee-inflicted damage. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1590422078311-B6AUBLIBRG2QYEXCJ9EI/F1.large.jpg)