Photo by Susulyka licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Take a look at a list of tree species from temperate Europe, North America, and Asia and you will notice a glaring disparity. Whereas North America and Asia are home to something like 1000 tree species each, Europe is home to just about 500 species. Why is this?

The answer may lie partly in the glacial history of the Northern Hemisphere as well as in some quirks of geology. Starting in the late Pliocene, roughly 3 million years ago, the Earth began to cool. As our planet entered into a epoch dominated by massive, continent-wide glaciers, life was responding accordingly.

Historically it was assumed that Europe lost many of its temperate tree species thanks to the east-west orientation of its mountain ranges. As glaciers advanced from the north, species were pushed farther and farther south until they hit physical barriers in the terrain like the Alps. With nowhere to go but up, many species that couldn’t handle either the rate of climate change or the altitude adjustment simply winked out of existence. Fossil evidence from Europe provides plenty of evidence that this region was once home to far more tree species, including relatives of sweetgum (Liquidambar spp.) and tulip trees (Liriodendron spp.) that are still present in North America, and umbrella pines (Sciadopitys spp.), which still exists in Asia. Many temperate tree species in North America and Asia were spared this fate because there were far fewer barriers to successful southern migrations.

This all sounds a bit too simple and indeed, recent studies suggest that it is. Though climate change, glaciers, and mountains certainly played a role in the differential extinction rates of European trees, the story is a bit more complicated than that. It turns out that the European mountain ranges don’t present as impenetrable of a barrier to plant migrations as was once thought. The fact that southern Europe and northern Africa share many similar taxa is proof of this. Instead, the amount of suitable habitat and land area available to trees migrating down from northern Europe may have played an even larger role in the extinction rate of European trees.

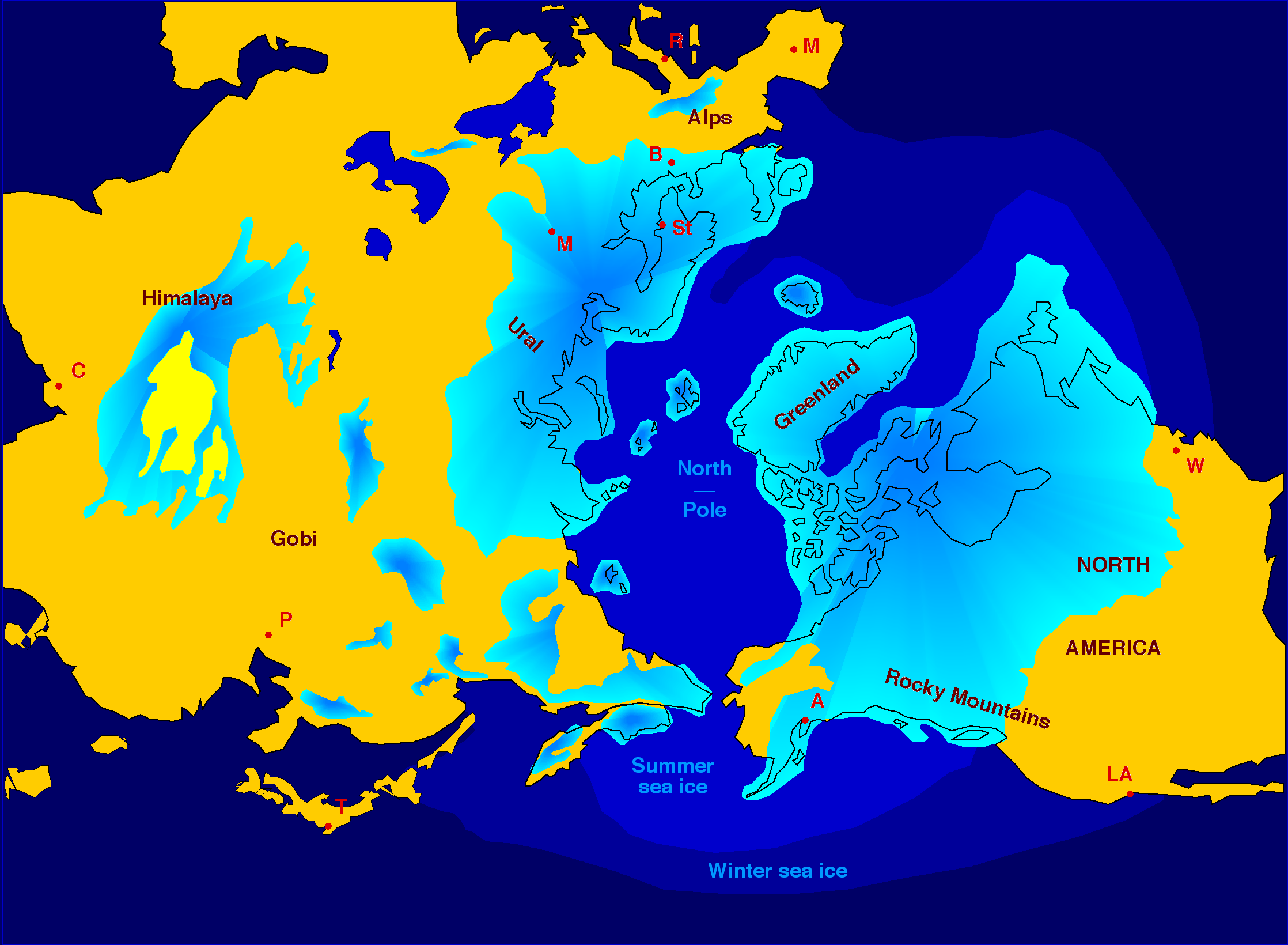

Extent of glacial coverage (blue) during the last ice age. Map by Hannse Grobe licensed under CC-BY-2.5

It is a well documented phenomenon in ecology that smaller areas of land support smaller numbers of species. This is the case for Pleistocene Europe. Suitable habitat for temperate tree species during this time would have largely consisted of three peninsulas (Iberia, Italy, and the Balkans) separated by the Mediterranian Sea. Each of these peninsulas boast mountain chains that would have offered small bands of suitable microclimates for temperate tree species to find refuge during glacial advance.

Pushed into tiny pockets of refugia, Europe’s temperate tree species would have been more vulnerable to extinction than tree species in North America and Asia, which had far more suitable habitat available to them in the southern portions of those continents. By looking at which taxa survived and which went extinct, patterns do start to emerge. Tree species that are widespread in Europe today are descendants of trees that were far more tolerant of cooler growing seasons and harsh winters than genera that went extinct. This likely reflects the fact that their ancestors were those species that found refuge high up in the mountains.

Alternatively, present-day Europe also boasts small pockets of what are termed “relictual genera,” which is a fancy way of saying species that were once more common in the past than they are today. These so-called relictual taxa have been found to be far more tolerant of drought than genera that went extinct. This likely reflects the fact that their ancestors found refuge in warmer, low-elevation habitats in southern Europe.

It appears that species on either end of the tolerance curves were the ones that won out in Europe’s extinction lottery. By tolerating either extreme cold or extreme drought, “stress tolerators” were able to not only survive repeated glaciation events, but also provide seed sources for those lineages following glacial retreat.

Only the species that were able to find suitable habitats in southern Europe’s glacial refugia were the ones that were able to recolonize the region after the Ice Age had ended. At this point in time, these are some of the best pieces of evidence we have in explaining the disparity in tree diversity between Europe, North America, and Asia. What’s more, I find disturbing trends in such extinctions because it wasn’t like the glaciers always wiped out species immediately. Instead, many species were able to survive glaciation but were pushed into smaller and smaller pockets of suitable habitat until relatively small disturbances pushed them over the edge.

Today, we humans are changing Earth’s climates at a rate that hasn’t been seen in over 50 million years and all the while we are fragmenting habitats more and more. What is going to happen to species living today in these tiny pockets?