Photo by Ignacio Escapa, Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio

Tomatillos and ground cherries just got a bit older. Okay, a lot older. Exquisitely preserved fossils from an ancient lake bed in Argentina are shining a very bright light on the genus Physalis and the family Solanaceae as a whole. Despite the importance of this plant family around the globe, little fossil evidence has ever been found. That is, until now.

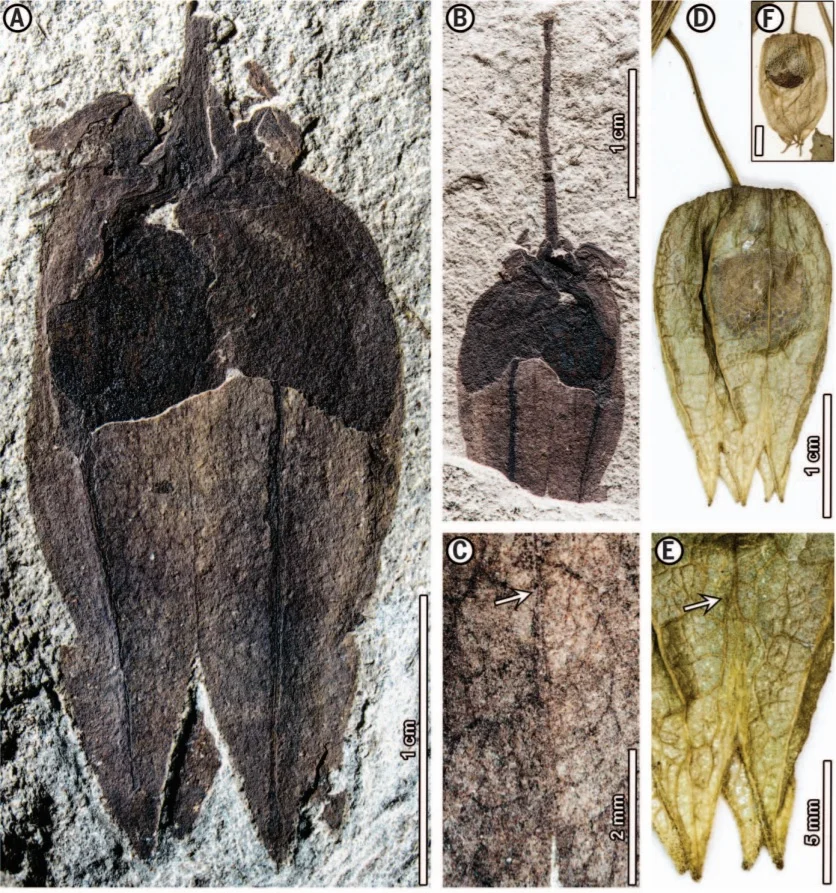

Dated at 52 million years old, these fossils paint a picture of a snapshot in the evolution of the genus Physalis. The fossils are remarkable, allowing for close inspection of minute details like vein structure. Because of the level of detail discernible, experts can say without a doubt that these fossils could be nothing else other than a species of Physalis.

One of the most interesting aspects of these fossils is their age. These sediments were deposited during the early Eocene Epoch. The fact that representatives of Physalis were alive and well during this time is quite remarkable. Because fossil evidence for Solanaceae has been so scarce, experts have had to rely solely on molecular dating in order to elucidate the origin and divergence of this family.

Original estimates placed the origin of Solanaceae at sometime around 30 million years before present. Physalis, being much more derived, was thought to have an even more recent emergence, some 9 million years ago. Boy, was that ever wrong. At 52 million years of age, we can now confidently say that Physalis is at least 43 million years older than previously thought. These findings also tell us that Solanaceae is even older still! If such a derived genus was thriving in Eocene Argentina 52 million years ago, basil members of the family must have gotten their start much earlier than we ever imagined.

Aside from big picture taxonomical revelations, the fossils also give us a window into the ecology of these ancient Physalis. The most obvious is that inflated bladder which surrounds the berry within. Though it is quite characteristic of this group, little attention has been paid to its function. The fact that the sediments in which they were preserved are of aquatic origin suggests that the inflated calyces may have evolved for aquatic seed dispersal. Experiments have shown that these structures on modern day ground cherries and tomatillos do in fact float, keeping the berry inside high and dry.

To think that all of this was brought to light from a handful of fossils. It just goes to show you the importance the paleontological discoveries can have. Just think of the countless amount of museum drawers and shelves that are chock full of interesting fossils waiting to be looked over. Who knows what they might tell us about our planet.

Photo Credit: Ignacio Escapa, Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio

Further Reading: [1]