Photo by Monteregina (Nicole) licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

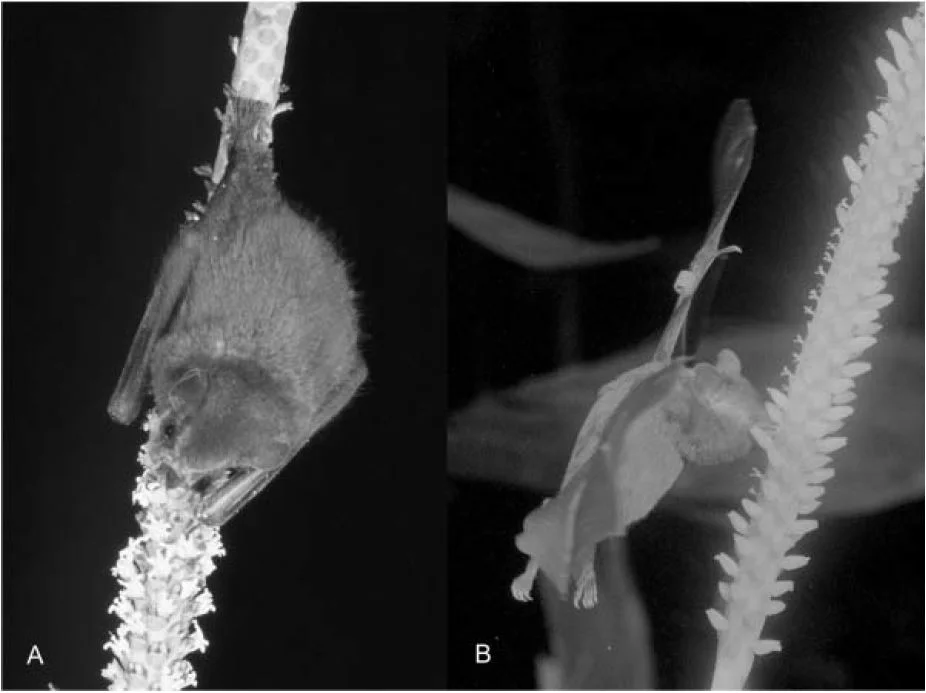

Getting pollen from one flower to another is the main reason why flowers exist in the first place. It makes sense then why pollen is often made readily available to pollinators. For many flowering plants, this means directing the pollen-filled anthers outward where they are ready to take advantage of floral visitors. The sunflower family (Asteraceae) does this a bit differently than most. They utilize a technique called secondary pollen presentation.

Though secondary pollen presentation is not unique to the sunflower family, their abundance on the landscape makes it super easy to observe. For the sunflower family, what looks like a single flower is actually an inflorescence made up of dense clusters of individual flowers. Each individual flower is roughly tubular in shape and, oddly enough, the anthers are tucked inside the tube facing the interior of the flower. It may seem odd to hide the anthers and their pollen inside of a tube until you see the blooming process sped up.

Photo by László Németh licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

The sunflower family actually relies on the female parts of the flower to bring the pollen out from the floral tube and into the environment where pollinators can access it. Members of the sunflower family are protandrous, meaning the male parts mature before the female parts. What this means is that the style of the flower can be involved in presenting pollen before it becomes receptive to pollen. This allows enough time for pollen presentation and reduces the likelihood of self pollination.

As the style elongates within the floral tube, one of two things can happen with the pollen inside. In some cases, the style acts like a tiny piston, literally pushing the pollen out into the world. In other cases, the style is covered in tiny, brush-like hairs that rake the pollen from the sides of the floral tube and carry it out as it emerges. In both cases, the style remains closed until enough time has passed for pollen to be taken away from the inflorescence.

After a period of time (which varies from species to species), the style splits at the tip and each side curls back on itself to reveal the stigmatic surface. Only at this point in time is are the female parts of the flower mature and ready to receive pollen. With any luck, much of the flowers own pollen would have been collected and taken away to other plants.

The combination of sequential blooming of individual flowers and protandry mean that members of the sunflower family both maximize their chances of pollination and reduce the likelihood of inbreeding. Add to that their ability to disperse their seeds great distances and myriad defense strategies and it should come as no surprise that this family is so darn successful. Get outside and try to witness secondary pollen presentation for yourself. Armed with a hand lens, you will unlock a world of evolutionary wonders!