Bullate leaves help the vine clasp to the tree as well as house ant colonies. Photo by Richard Parker licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The dogbane family, Apocynaceae, comes in many shapes, sizes, and lifestyles. From the open-field milkweeds we are most familiar with here in North America to the cactus-like Stapeliads of South Africa, it would seem that there is no end to the adaptive abilities of this family. Being an avid gardener both indoors and out, the diversity of Apocynaceae means that I can be surrounded by these plants year round. My endless quest to grow new and interesting houseplants was how I first came to know a genus within the family that I find quite fascinating. Today I would like to briefly introduce you to the Dischidia vines.

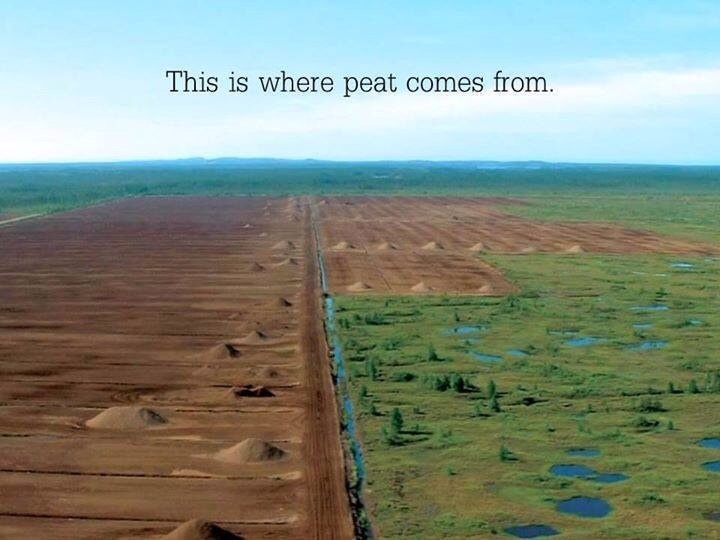

The genus Dischidia is native to tropical regions of China. Like its sister genus Hoya, these plants grow as epiphytic vines throughout the canopy of warm, humid forests. Though they are known quite well among those who enjoy collecting horticultural curiosities, Dischidia as a whole is relatively understudied. These odd vines do not attach themselves to trees via spines, adhesive pads, or tendrils. Instead, they utilize their imbricated leaves to grasp the bark of the trunks and branches they live upon.

The odd, bulb-like leaves of the urn vine (Dischidia rafflesiana) Photo by Bernard DUPONT licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

One thing we do know about this genus is that most species specialize in growing out of arboreal ant nests. Ant gardens, as they are referred to, offer a nutrient rich substrate for a variety of epiphytic plants around the world. What's more, the ants will visciously defend their nests and thus any plants growing within.

The flowers of Dischidia ovata Photo by Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Some species of Dischidia take this relationship with ants to another level. A handful of species including D. rafflesiana, D. complex, D. major, and D. vidalii produce what are called "bullate leaves." These leaves start out like any other leaf but after a while the edges stop growing. This causes the middle of the leaf to swell up like a blister. The edges then curl over and form a hollow chamber with a small entrance hole.

Photo by Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

These leaves are ant domatia and ant colonies quickly set up shop within the chambers. This provides ample defense for the plant but the relationship goes a little deeper. The plants produce a series of roots that crisscross the inside of the leaf chamber. As ant detritus builds up inside, the roots begin to extract nutrients. This is highly beneficial for an epiphytic plant as nutrients are often in short supply up in the canopy. In effect, the ants are paying rent in return for a place to live.

Growing these plants can take some time but the payoff is worth. They are fascinating to observe and certainly offer quite a conversation piece as guests marvel at their strange form.

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

Further Reading: [1]