The time has finally come! In Defense of Plants: An Exploration into the Wonder of Plants is now in stores. I thank everyone who pre-ordered a copy of the book. They should be on their way! I still can’t believe this is a reality. I always knew I wanted to write a book and I am eternally grateful to Mango Publishing for giving me this opportunity.

In Defense of Plants is a celebration of plants for the sake of plants. There is no denying that plants are extremely useful to humanity in many ways, but that isn’t why this exist. Plants are living, breathing, self-replicating organisms that are fighting for survival just like the rest of life on Earth. And, thanks to their sessile habit, they are doing so in remarkable and sometimes alien ways.

One of the best illustrations of this can be found in Chapter 3 of my new book: “The Wild World of Plant Sex.” Whereas most of us will have a passing familiarity with the concept of pollination, we have only really scratched the surface of the myriad ways plants have figured out how to have sex. Some plants go the familiar rout, offering pollen and nectar to floral visitors in hopes that they will exchange their gametes with another flower of the same species.

Others have evolved trickier means to get the job done. Some fool their pollinators into thinking they are about to get a free meal using parts of their anatomy such as fake anthers or by offering nectar spurs that don’t actually produce nectar. Some plants even pretend to smell like dying bees to lure in scavenging flies. Still others bypass food stimuli altogether and instead smell like receptive female insects in hopes that sex-crazed males won’t know the difference.

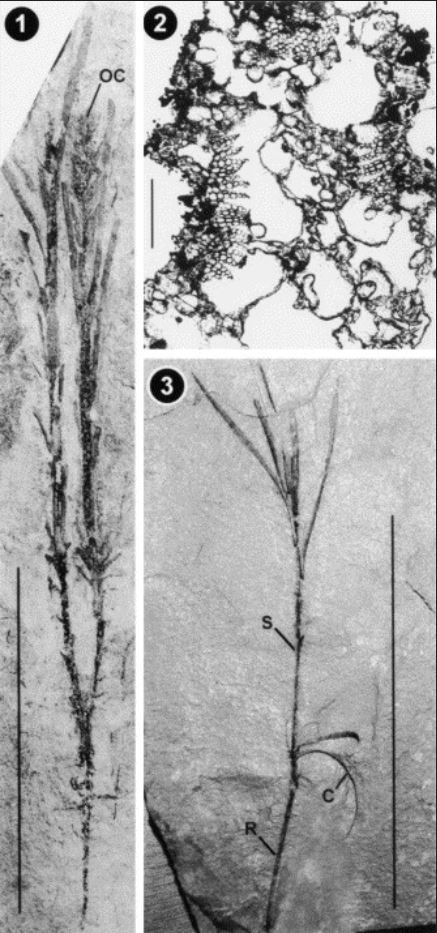

Pollination isn’t just for flowering plants either. In In Defense of Plants I also discuss some of the novel ways that mosses have converged on a pollination-like strategy by co-opting tiny invertebrates that thrive in the humid microclimates produced by the dense, leafy stems of moss colonies.

This is just a taste of what is printed on the pages of my new book. I really hope you will consider picking up a copy. To those that already have, I hope you enjoy the read when it arrives! Thank you again for support In Defense of Plants. You are helping keep these operations up and running, allowing me to continue to bring quality, scientifically accurate botanical content to the world. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.