Photo by Andrew Ward licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

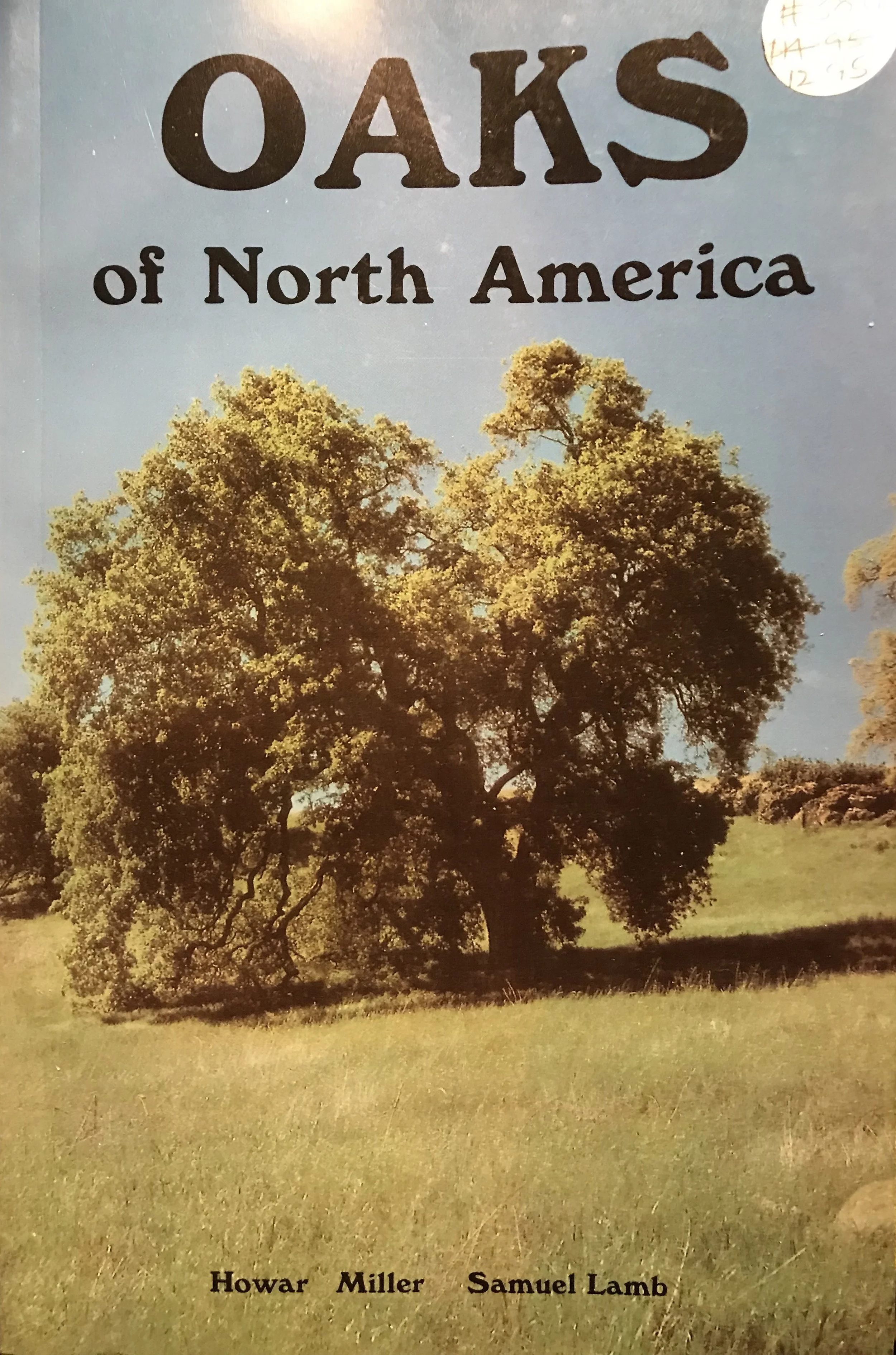

I am a sucker for smoketrees (Cotinus spp.). These members of the cashew family (Anacardiaceae) are a common sight around my town and really put on a dazzling show from late spring through fall. When I finally got around to putting a name to these trees, I was a little bit bummed to realize that all of the specimens in town are representatives of the Eurasian species, Cotinus coggygria, but it didn’t take me long to find out that North America has it’s own fascinating representative of the genus.

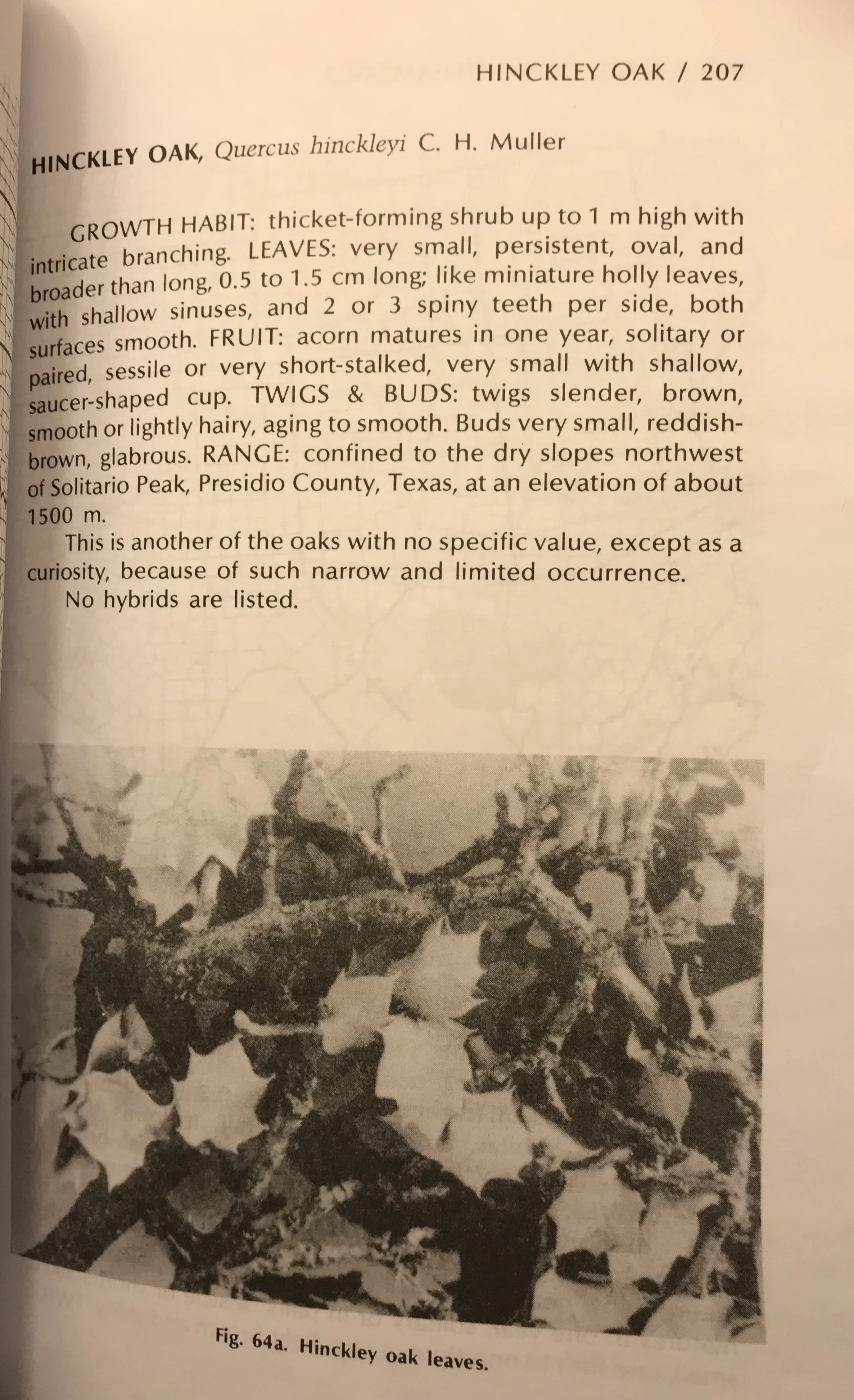

The American smoketree (Cotinus obovatus) is not terribly common in the wild or cultivation. Today, it exhibits a suffuse distribution through parts of southern North America, with disjunct populations occurring along the Ozark Plateau of Arkansas and Missouri, the Arkansas River in eastern Oklahoma, the Cumberland Plateau in northeastern Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia, and the Edwards Plateau in west-central Texas. The major habitat feature that unites these populations is soil. All of them are said to grow on rocky, calcareous soils prone to drought.

Photo by Megan Hansen licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

It is an interesting distribution to say the least. I haven’t found too much in the way of an explanation for why the American smoketree is limited to calcareous soils in the wild. Apparently it is fairly adaptable to different soil types in cultivation. Perhaps competition with other species limits this tree to harsh conditions. It isn’t a big species by most standards. The American smoketree generally produces multiple stems and only occasionally reaches heights of 30 feet (9 meters) or more in most circumstances. One phrase that gets repeated with some frequency is that the American smoketree likely represents a relictual species.

Though hard to prove without ample fossil evidence, it seems many experts believe that American smoketrees (and the genus Cotinus in general) were far more common and widespread in the past than they are today. Indeed, the fossil remains of a species named Cotinus cretaceus (sometimes C. cretacea) were found in Alaska and date back to the late Cretaceous. Given that the American smoketree’s closest living relatives are found throughout parts of Europe and Asia, such evidence suggests that this genus spread into North America during a period when land bridges connected the two continents and has since been reduced to scattered populations of this single North American species.

Photo by Andrey Zharkikh licensed under CC BY 2.0

European colonization of North America did not help the American smoketree either. American smoketree sap can be processed into a yellow dye, which was highly coveted during the American Civil War. Its rot-resistant wood was also widely used for fence posts. At least one source I found indicated that the tree was cut to near extirpation in many areas for these reasons. Luckily today, with harvesting pressures largely a thing of the past, the American smoketree has rebounded enough that it is currently considered a species of least concern.

The American smoketree has also benefited from some minor popularity in cultivation. Like its Eurasian cousins, the appeal of this species comes from its colorful foliage, wonderfully flaky bark, and billowy inflorescences. Its egg-shaped leaves emerge in spring and are silky and pink. As spring gives way to summer, the leaves gradually turn a pleasing shade of blueish-green. Come fall, the leaves paint the landscape in bright red until they are shed. Late spring is generally the blooming time for American smoketree.

Photo by geneva_wirth licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Photo by peganum licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Its tiny, inconspicuous flowers are borne on large, branching panicles. Each panicle is covered in tiny hairs that apparently continue to grow well after the flowers have been pollinated. This is where the name smoketree comes from. From afar, a tree covered in panicles looks as if it is billowing dense clouds of smoke from its canopy. The whole spectacle is stunning to say the least and I just wish this species was more popular than its cousins.

All in all, the American smoketree is a truly interesting species. From its fractured distribution and curious history to its status as an obscure native tree in cultivation, there are a lot of reasons to love this species. Though related to plants like poison ivy (Toxicodendron spp.), smoketrees only rarely cause dermatitis in particularly susceptible individuals. I hope I get the chance to see an American smoketree in the wild some day.

![Current range of dwarf sumac (Rhus michauxii). Green indicates native presence in state, Yellow indicates present in county but rare, and Orange indicates historical occurrence that has since been extirpated. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1609184191069-557J58DPH2J8L74Y1O06/Rhus+michauxii.png)

![[source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1533585937843-ART57F0111IK2ZJH43ZX/late+fall.JPG)