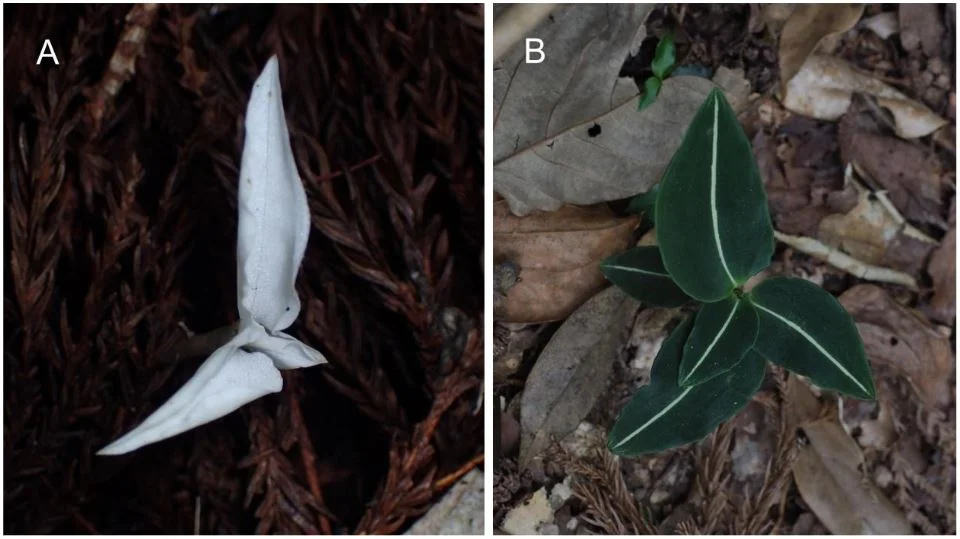

Yoania japonica. Photo by Qwert1234 licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Historically, non-photosynthetic plants were defined as saprotrophs. It was thought that, like fungi, such plants lived directly off of decaying materials. Advances in our understanding have since revealed that parasitic plants don’t do any of the decaying themselves. Instead, those that aren’t direct parasites on the stems and roots of other plants utilize a fungal intermediary. We call these plants mycoheterotrophs (fungus-eaters). Despite recognition of this strangely fascinating relationship, we still have much to learn about what kinds of fungi these plants parasitize and where most of the nutritional demands are coming from.

It is largely assumed that most mycoheterotrophic plants are parasitic on mycorrhizal fungi. This would make them indirect parasites on other photosynthetic plants. The mycorrhizal fungi partner with photosynthetic plants, exchanging soil nutrients for carbon made by the plant during photosynthesis. However, this is largely assumed rather than tested. New research out of Japan has shown a light on what is going on with some of these parasitic relationships and the results are a bit surprising. What’s more, the methods they used to better understand these parasitic relationships are pretty clever to say the least.

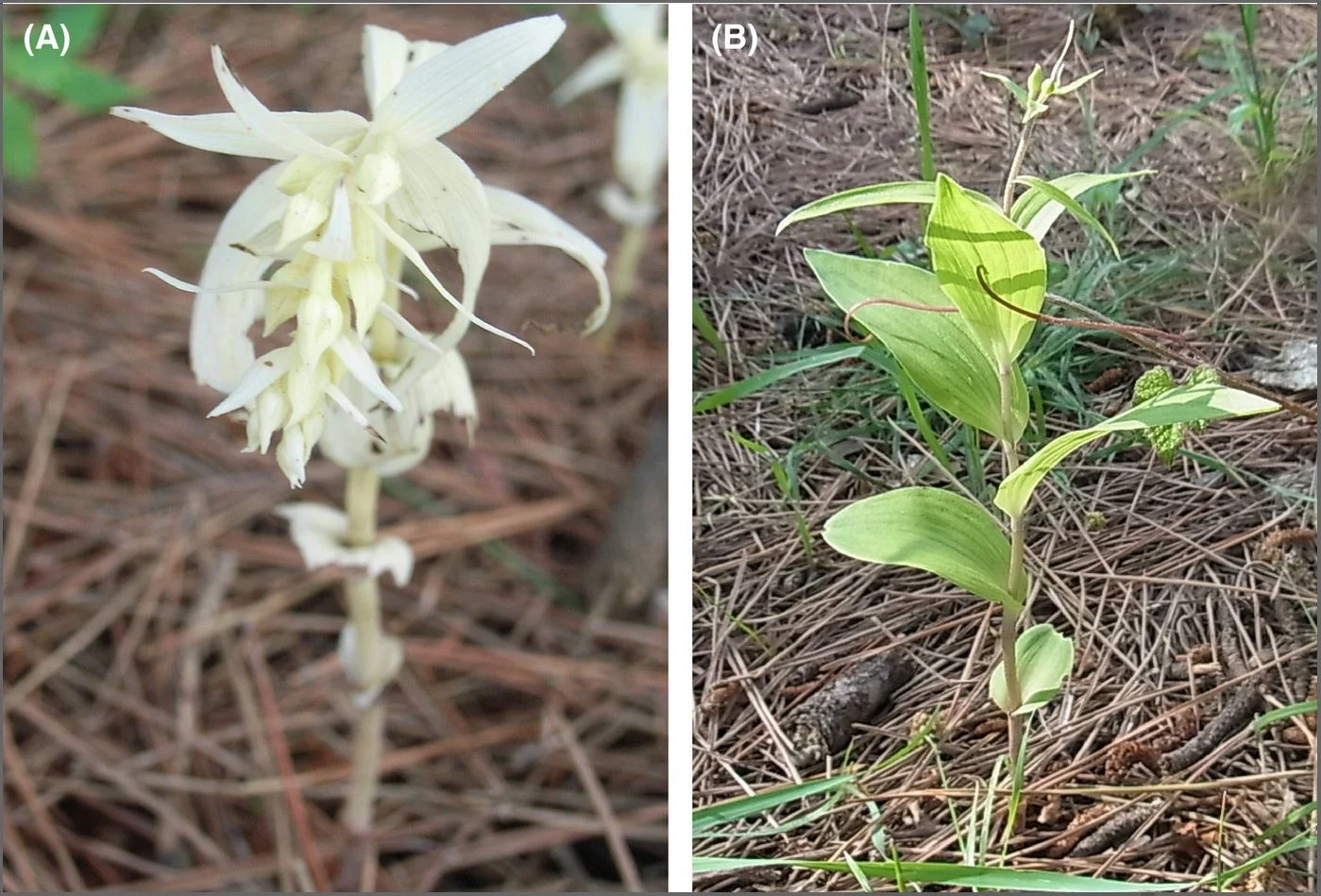

Cyrtosia septentrionalis Photo by Qwert1234 licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Photosynthesis involves the uptake of and subsequent breakdown of CO2 from the atmosphere. The carbon from CO2 is then used to build carbohydrates, which form the backbone of most plant tissues. Not all carbon is created equal, however, and by looking at ratios of different carbon isotopes in living tissues, scientists can better understand where the carbon came from. For this research, scientists utilized an isotope of carbon called 14C.

Eulophia zollingeri photo by Vinayraja licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

14C is special because it is not as common in our atmosphere as other isotopes of carbon such as 12C and 13C. One of the biggest sources of 14C in our atmosphere were nuclear bomb explosions. From the 1950’s until the Partial Nuclear Test Ban in 1963, atomic bomb tests were a regular occurrence. During that time period, the concentration of 14C in our atmosphere greatly increased. Any organism that was fixing carbon into its tissues during that span of time will contain elevated levels of 14C compared to the other carbon isotopes. Alternatively, anything fixing carbon today, say via photosynthesis, will have considerably reduced levels of 14C in its tissues.

Gastrodia elata Photo by Qwert1234 licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

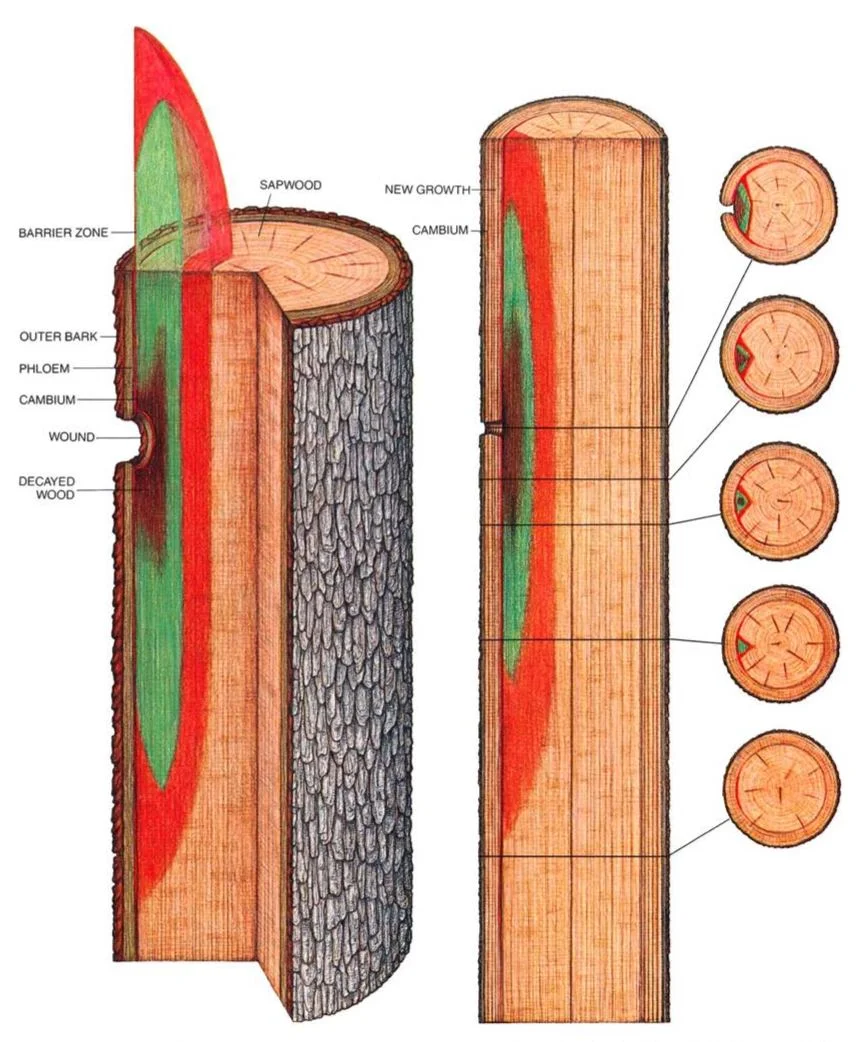

By looking at the ratios of 14C in the tissues of parasitic plants, scientists reasoned that they could assess the age of the carbon being utilized. If more 14C was present, the source of the carbon could not come from today’s atmosphere and therefore not from recent photosynthesis. Instead, it would have to come from older sources like decaying wood of long-dead trees. In other words, if parasitic plants were high in 14C, then the scientists could reasonably conclude that they were parsitizing wood-decaying saprotrophic fungi. If the plants were high in 12C or 13C, then they could conclude that they were partnering with mycorrhizal fungi instead, which were obtaining carbon from present-day photsynthesis.

The researchers looked at 10 different species of parasitic plants across Japan, most of which were orchids. They analyzed their tissues and ran analyses on the carbon molecules within. What they found is that 6 out of the 10 plants contained much higher levels of 12C and 13C in their tissues, which points to mycorrhizal fungi as their host. However, for the 4 remaining species (Gastrodia elata, Cyrtosia septentrionalis, Yoania japonica and Eulophia zollingeri), the ratios of 14C were considerably higher, meaning their host fungi were eating dead wood, not partnering with photosynthetic plants near by.

Indeed, it appears that at least some mycoheterotrophic plants are benefiting from saprotrophic rather than mycorrhizal fungi. Those early assumptions into the livelihood of such plants were not as far off the mark after all. This is very exciting research that opens the door to a much deeper understanding of some of the strangest plants on our planet.

LEARN MORE ABOUT MYCOHETEROTROPHIC PLANTS IN EPISODE 234 OF THE IN DEFENSE OF PLANTS PODCAST

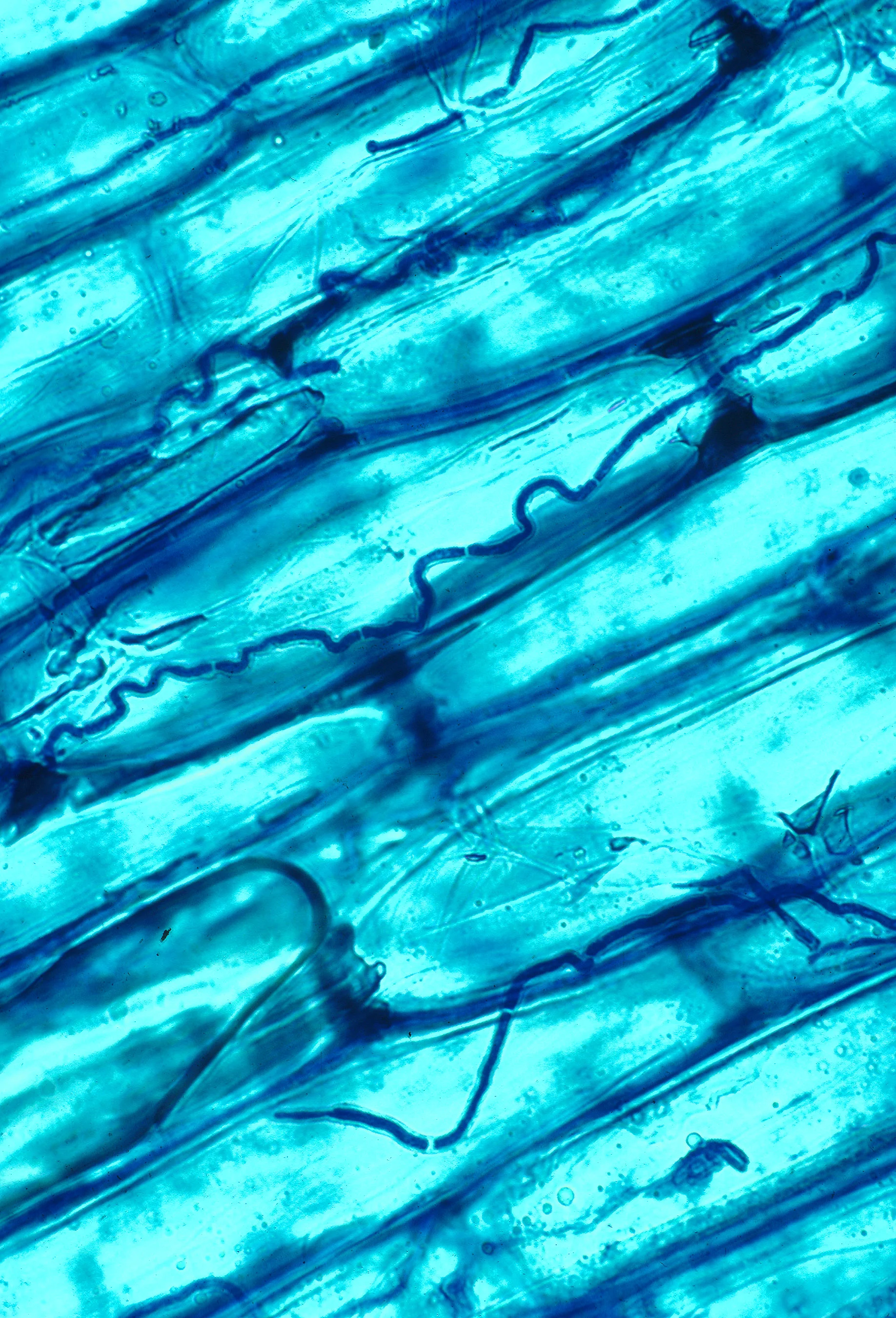

![Stems climbing on fallen dead wood (a) or on standing living trees (b). A thick and densely branched root clump (c) and thin and elongate roots (d) [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1518471929195-C99KP24U24J238YMX055/myco+roots.JPG)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1485992214448-W3DN42037E3R1Z3OYFIJ/image-asset.jpeg)